How often and in what circumstances do interest groups influence US national policy outcomes? In this article, I introduce a new method of assessing influence based on the judgments of policy historians. I aggregate information from 268 sources that review the history of domestic policy making across 14 domestic policy issue areas from 1945 to 2004. Policy historians collectively credit factors related to interest groups in 385 of the 790 significant policy enactments that they identify. This reported influence occurs in all branches of government, but varies across time and policy area. The most commonly credited form of influence is general support and lobbying by advocacy organizations. I also take advantage of the historians’ reports to construct a network of 299 specific interest groups credited with policy enactments. The interest group influence network is centralized, with some ideological polarization. The results demonstrate that interest group influence may be widespread, even though the typical tools that we use to assess it are unlikely to find it.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Public policy is the ultimate output of a political system and influencing policy is the main intent of interest groups. Yet interest group scholars have had difficulty consistently demonstrating interest group influence on policy. As a result, we are left with incomplete answers to some basic and important questions: How often do interest groups influence policy change? In what venues and what policy areas is interest group influence most common? Is interest group influence increasing or decreasing? Do certain types of organizations or tactics influence policy more than others?

This article addresses all of these questions by relying on the judgments of historians of American domestic policy. It reviews the perceived influence of interest groups on significant policy changes enacted by the American federal government since 1945 in 14 policy areas, enabling an assessment of the frequency of interest group influence as well as variation across venues, issue areas, groups, tactics, and time periods. Footnote 1 Rather than offer definitive answers, this offers a new type of appraisal of interest group influence. It aggregates the explanations for significant policy enactments found in qualitative histories of individual issue areas such as environmental policy and transportation policy. Footnote 2 The authors of these histories typically do not set out to assess interest group influence. They intend to produce narrative accounts of policy development. In the process, they identify the actors most responsible for policy change and the political circumstances that made policy change likely, including but not limited to interest group activity. Assembling their explanations offers a new perspective on the role of interest groups in policy change.

I use 268 historical accounts of the policy making process, each covering 10 years or longer of post-1945 policy history, as the raw materials for the analysis. Footnote 3 By using secondary sources, I can aggregate information about 790 US federal policy enactments that were considered significant by policy historians, including laws passed by Congress, executive orders by the President, administrative agency rules and federal court decisions. Footnote 4 Policy historians do not assume that every interest group can be effective or that every group is influential for the same reasons. Their research enables a look at differences in policy influence across groups and contexts. They assess the role of interest groups as one piece in a multifaceted policy making system.

In what follows, I track when, where and how interest groups influenced policy change, according to policy historians. First, I review the findings and the research strategies pursued in scholarship on interest group influence and advocate the use of policy histories. Second, I describe my method of aggregating explanations for policy change from policy histories. Third, I review the factors related to interest groups and the types of groups that are credited in explanations for policy change. Fourth, I investigate variation in interest groups influence across time and issue areas. Fifth, I construct and analyze a network of specific interest groups credited with policy enactments, including its structure and the particular interest groups that are central. Sixth, I review the limitations of using the collective judgments of policy historians to assess interest group influence. I conclude with an evaluation of scholars’ current strategies for assessing influence, arguing that current research might not uncover the kinds of influence noted by policy historians.

Studies of the policy process indicate that interest groups often play a central role in setting the government agenda, defining options, influencing decisions and directing implementation (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993; Berry, 1999; Patashnik, 2003). In their meta-analysis of studies of influence, Burstein and Linton (2002) show that interest groups are often found to have a substantial impact on policy outcomes. Yet most studies of influence look at particular issue areas and organizations, rather than generalize across a large range of cases (Baumgartner and Leech, 1998).

Studies of influence that do attempt to generalize suffer from the inherent difficulty of measuring influence. One type of study uses surveys or interviews with interest group leaders or lobbyists, mostly relying on self-reports of success (Holyoke, 2003; Heaney 2004). This tells us only what group tactics are associated with success as perceived by each group. A second type of study selects a measure of the extent of interest group activity, especially Political Action Committee (PAC) contributions or lobbying expenditures, and associates it with legislative outcomes. The large literature on the role of PAC contributions on roll call votes found no consistent effects on votes (Wawro, 2001), but there is some evidence that contributions may raise the level of involvement in legislation already supported by the legislator (Hall and Wayman, 1990). A third type of study changes the dependent variable from policy influence to lobbying success. This allows scholars to assess who is on the winning side of policy debates based on interest group coalition characteristics (Baumgartner et al, 2009; Mahoney, 2008). Yet these assessments do not incorporate the many other factors unrelated to interest groups that predict the success and failure of policy initiatives.

Research that has generated consistent evidence of influence is rare and tends to focus on narrow policy goals rather than significant policy enactments. Activity by groups with non-ideological or uncontroversial causes, for example, may have some effect (Witko, 2006). Business is most effective when it has little public or interest group opposition (Smith, 2000). Resources spent directly to procure earmarks can be effective (de Figueiredo and Silverman, 2006). General studies of interest group influence have been able to definitively demonstrate only conditional and small effects, often on minor policy outcomes. Even studies of lobbying success, rather than influence, tend to demonstrate the potential to stop policy change rather than to bring it about (Baumgartner et al, 2009). Despite the many case studies that find evidence of interest group influence on major laws (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993), administrative actions (Patashnik, 2003) and court decisions (Melnick, 1994), aggregate studies of influence based on the resources spent by each side fail to demonstrate that interest group activity can lead to major policy enactments.

Scholars have also sought to use network analysis to understand how interest group relationships might lead to policy influence. Heinz et al (1993), for example, find that most policy conflicts feature a ‘hollow core’, with no one serving as a central player, arbitrating conflict. Grossmann and Dominguez (2009), in contrast, find a core-periphery structure to interest group coalitions, with some advocacy groups, unions and business peak associations playing central roles. Yet most network analyses are based on endorsement lists or reported working relationships, rather than influence. Footnote 5 There has been no effort to look at a large number of significant policy enactments over a long historical period and assess the pattern of interest group influence.

In contrast to scholarship on interest groups, policy histories do not involve a search for evidence that interest groups are influential. Interest groups only enter the explanation to the extent that a policy historian telling the narrative of how and why a policy change came about is convinced that the role of interest groups was important. These authors rely on their own qualitative research strategies to identify significant actors and circumstances. The 268 sources used here quote first-hand interviews, media reports, reviews by government agencies and secondary sources. The authors of these books and articles were issue area specialists, primarily scholars at universities, but also including some journalists, think tank analysts and policymakers. Footnote 6 They select their explanatory variables based on the plausibly relevant circumstances surrounding each policy enactment with attention to the factors that seemed different in successes than failures, though they rarely systematize their selection of causal factors across cases. I rely on the judgments of these experts in each policy area, who have already searched the most relevant available evidence, rather than impose one standard of evidence across all cases and independently conduct my own analysis.

One benefit of such an approach is that policy historians do not come to the research with the baggage of interest group theory or intellectual history. For example, they do not necessarily assume that interest groups have difficulty overcoming collective action problems or that resources are the main advantage of some interests over others. Another benefit is that they look over a long time horizon, rather than a single congress or presidential administration. This allows them to consider how policy developed and to review many original inside documents from policymakers. Policy historians cannot be said to produce the only reasonable account of interest group influence, but they collectively offer a different kind of evidence based on an independent set of investigations that can be productively compared with the findings from interest group research.

The literature that I compile does not share a single theoretical perspective on the policy process. The authors see themselves as scholars of the idiosyncratic features of each policy area, as well as observers of case studies of the general features of policy making. To the extent that policy history offers a unique theoretical perspective on interest group influence, it points to the interdependence of interest groups with their political context and the vastly unequal capacity for influence among groups. Scholars of interest groups are sensitive to the political context that groups face, but they would be less likely to consider whether interest groups lack influence in certain time periods or issue areas because other actors predominate. Policy historians are just as likely to point to a powerful administrative agency leader or long-serving member of Congress as to assign credit to interest groups. Scholars of interest groups also look at differences in access or capacity across groups, but they rarely consider the possibility that only a few large, well-known groups have what it takes to help alter policy outcomes. Just as policy historians ignore most members of Congress in their retelling of the events surrounding policy development, most interest groups and lobbyists never do enough to leave their imprint on policy history.

To assess interest group influence on policy enactments, I use in-depth narrative accounts of policy development. Policy historians catalog the important output of the policy making process and attempt to explain how, when and why public policy changes. David Mayhew (2005) uses policy histories to construct his list of landmark laws; he defends the histories as more conscious of the effects of public policy and less swept up by hype from political leaders than contemporary judgments (Mayhew, 2005, pp. 245–252). Since Mayhew completed his review in 1990, there has been an explosion of scholarly output on policy area history. Yet scholars have not systematically returned to this vast trove of information. My analysis expands Mayhew's (2005) source list by more than 200 per cent.

In what follows, I compile information from 268 books and articles that review at least one decade of policy history since 1945. Footnote 7 The sources cover the history of one of 14 domestic policy issue areas from 1945 to 2004: agriculture, civil rights & liberties, criminal justice, education, energy, the environment, finance & commerce, health, housing & community development, labor & immigration, science & technology, social welfare, macroeconomics, and transportation. Footnote 8 This excludes defense, trade and foreign affairs, but covers the entire domestic policy spectrum. Footnote 9 I obtained a larger number of resources for some areas than others but analyzing additional volumes covering the same policy area reached a point of diminishing returns. In the policy areas where I located a large number of resources, the first five resources covered most of the significant policy enactments. The full list of sources, categorized by policy area, is available on my web site. Footnote 10

The next step was reading each text and identifying significant policy enactments. I primarily used 10 research assistants, training them to identify policy changes. Other assistants coded individual books. I followed Mayhew's (2005) protocols but tracked enacted presidential directives, administrative agency actions and court rulings along with legislation identified by each author as significant. I include policy enactments when any author indicated that the change was important and attempted to explain how or why it occurred. As a reliability check, pairs of assistants assessed the same books and identified 95 per cent of the same significant enactments. For each enactment, I coded whether it was an act of Congress, the President, an administrative agency or department, or a court.

I coded any mentions of factors related to interest groups that may influence policy change. Coders asked themselves 61 questions about each author's explanation of each change from a codebook. Thirteen of these questions involved interest groups. For example, I coded whether authors referred to Congressional lobbying, protest or group mobilization, even without naming specific groups. Some authors also referred to categories of interest groups (such as an industry or ‘environmentalists’) without mentioning specific organizations. I tracked all of these references to interest groups in author explanations for policy enactments. Interest groups include corporations, trade associations, advocacy groups or any other private sector organizations. I record 13 dichotomous indicators of the type of interest group influence and the type of interest group cited.

This produces a database of where interest group factors were credited by each author. Coders of the same volume reached agreement on more than 95 per cent of all codes. Footnote 11 Comparisons of different author explanations for the same enactment showed that some authors recorded more explanatory factors than others. In the results below, I aggregate explanations across all authors, considering interest group factors relevant when any source considered them part of the reason for an enactment. I review potential biases in policy histories and potential problems with my aggregation methods in the limitations section of the article.

A similar method was successfully used by Eric Schickler (2001) to assess theories of changes in Congressional rules. The method is also related to the analysis performed by John Kingdon (2003), but his analysis relies on his own first-hand interviews, whereas this article compiles the first-hand research of many different authors. Like meta-analysis, the method aggregates findings from an array of sources to look for patterns of findings. In this respect, it is similar to Burstein and Linton's (2002) study of 53 journal articles. As the original works in this case are case studies or historical narratives, however, the results are descriptive and do not assume uniformity of method.

Several robustness checks confirmed that using qualitative accounts of policy history produces reliable indicators. First, different authors produce similar lists of relevant circumstantial factors in each enactment. Second, authors covering policy enactments outside of their area of focus (such as health policy historians explaining the political process behind general tax laws) also reach most of the same conclusions about what circumstances were relevant as specialist historians. Third, there were few consistent differences based on whether authors used interviews, quantitative data or archival research; whether the authors came from political science, policy, law, sociology, economics, history or other departments; or how long after the events took place the sources were written.

According to policy historians, interest groups are involved in significant policy enactments quite often. Interest groups were partially credited with 279 significant new laws passed by Congress (54.8 per cent of all significant legislative enactments), 31 significant executive orders (41.3 per cent of the total), 35 significant administrative agency rules (39.3 per cent of the total) and 46 significant judicial decisions (36.8 per cent of the total). Policy historians thus credit interest group factors with playing a role in policy making in every type of federal policy making venue, but most often in Congress. Interest group activities are sometimes mentioned as the sole explanatory factor in these explanations; more commonly, they are mentioned in combination with other factors such as focusing events, media coverage, negotiations among government officials and the support of specific policymakers.

Even though there are important differences in explanatory factors for policy enactments in different branches of government, interest groups are commonly credited actors in all three branches. In one instance, Studlar (2002) describes a case of brinksmanship between administrative agencies and regulated corporate interests over the broadcast ban on tobacco advertising. In another context, Studlar (2002) reports, the administration partnered with interest groups in the legislature by acting to classify tobacco as a carcinogen: ‘Second hand smoke became a major issue after the Surgeon General's report of 1986. In an effort to help classify this aspect of tobacco and to get the ball rolling with interest groups and the promotion of legislation, the EPA took control’. Interest groups are also credited with actions by the President, such as Bill Clinton's guidelines on religious expression in schools (Fraser, 1999, p. 205). Interest groups are credited with policy changes in the courts as well, even though courts are the venue where the average interest group is less involved (Schlozman and Tierney, 1986). Most interest groups credited with court rulings brought the relevant case to the courts, though some only authored influential amimus briefs.

Table 1 reports the specific types of interest group factors mentioned in explanations for policy change. General interest group support was mentioned in conjunction with 22 per cent of policy enactments (this was a residual category, when no specific tactics were referenced). Most frequently, a specific organization was referenced for developing a proposal or for their work on behalf of policymakers. On other occasions, a broad coalition was involved in promoting policy change.

Interest group influence is reportedly more common in some policy areas than others. Table 3 reports the percentage of policy changes involving interest groups by major domestic policy domain. Interest groups were most frequently involved in policy changes in the environment and civil rights & liberties, where they were partially credited with more than two-thirds of policy changes. This is unsurprising given the large related advocacy communities. Interest groups like the American Farm Bureau and the Farmers Union were commonly credited with agriculture policy changes. Transportation policy is more frequently associated with corporate influence than other sectors. Factors related to groups were also credited in at least half of policy enactments in housing & development, labor & immigration, and macroeconomics. Groups were least commonly credited with policy change in criminal justice, but they reportedly played a role in at least 30 per cent of significant enactments in all areas. Reported group influence varies widely across issue areas but is never absent. Advocacy organizations were the most frequently credited type of interest group in most issue areas, although corporations and their associations were more common in energy, finance, macroeconomics, science and transportation. These issue areas feature substantial government financing and business regulation, but have not stimulated as many prominent advocacy groups.

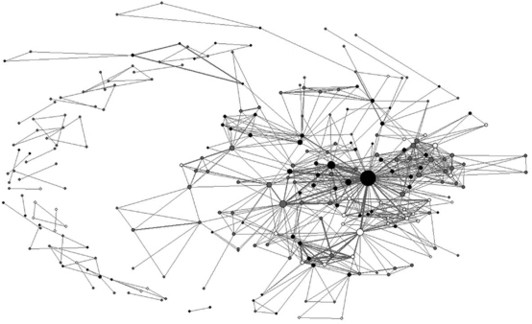

A few important features of the network are visible from the figure. First, the figure has a core set of interest groups closely connected to one another and a larger periphery of less connected groups. This is consistent with interest group legislative networks (Grossmann and Dominguez, 2009), but less consistent with networks of working relationships among lobbyists (Heinz et al, 1993). Second, conservative groups are not as common as liberal groups and are less central in the overall network. This is consistent with the prominence of liberal issue groups in the advocacy community (Berry, 1999; Grossmann, 2012). Third, there is some ideological clustering, separation between conservative and liberal groups. This is consistent with interest group electoral networks but not with their legislative networks (Grossmann and Dominguez, 2009).

Table 4 reports some quantitative measures of these features of the network, alongside lists of the most central groups in the network. Density is the average number of ties between all pairs of nodes. The low number signifies that most interest groups are not jointly enacting policy with most others; the average group has a small number of ties. The clustering coefficient measures the extent to which actors create tightly knit groups characterized by high density of ties. The clustering coefficient is above one, indicating a moderate degree of clustering. This means that groups that are connected with one another are also likely to be connected to the same other groups. The ideological version of the external–internal index is calculated by subtracting the number of ties within conservative and liberal sets of groups from the number of ties between different ideological groups over the total number of ties. This index measures the extent to which ties are disproportionately across ideological sectors (positive) or within ideological sectors (negative). The result confirms that there is an ideological division between liberal and conservative groups, with ideologically like-minded groups much more likely to be jointly enacting policy together.

Table 4 Interest group influence network characteristicsThe table also includes two measures of the most central actors in the network and the overall centralization of the network. Degree centralization measures the extent to which all ties in the network are to a single actor. Betweeness centralization measures how closely the networks resemble a system in which a small set of actors appears between all other actors in the network that are not connected to one another. Degree centralization is somewhat high and betweeness centralization is quite high, indicating that interest groups in the center of the network help bridge gaps between other unconnected groups in the network.

The lists of central actors contain substantial overlap. Reported influence on national policy is highly concentrated among a small number of well-known interest groups, many of which worked to enact the same policies. The central members are diverse. They include advocacy organizations representing large social groups and large peak associations. The role of the intergovernmental lobby is also important. Footnote 15 Nearly all of the organizations central to this influence network are also among the most prominent interest groups in media coverage and the most involved in policy making venues (see Grossmann, 2012). Over the full time period covered by the policy histories, 1945–2004, these groups were among the most important in driving policy change. Although there are more single-issue groups credited with policy change in more recent years, there is a striking consistency to the most credited broad actors over the six decades.

I find extensive reports of interest group influence in federal policy change since 1945 in historical accounts of particular policy areas. Interest group influence is reportedly widespread across all branches of government and in most policy areas. This matches the findings of previous literature reviews (Baumgartner and Leech, 1998; Burstein and Linton, 2002), but is somewhat inconsistent with the literature seeking to tie particular interest group tactics to policy success (Wawro, 2001; Baumgartner et al, 2009). Policy historians collectively endorse the conventional wisdom that interest groups influence policy change, rather than some of the counterintuitive findings from quantitative attempts to isolate the role of interest group resources or strategies on policy outcomes.

The most common interest group factor mentioned by historians of policy change was general support. This often included idea development, public support and advocacy. Congressional lobbying, generated constituent pressure and research were also somewhat commonly cited tactics. The most frequently credited types of interest groups were advocacy organizations, including ideological and single-issue groups as well as identity groups. According to historians of policy change, these groups were partially responsible for more than one-third of all significant post-war policy changes. Academics and business interests, especially industry trade associations and peak associations, were also judged important.

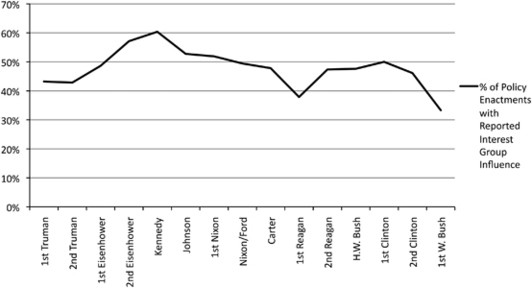

Surprisingly, interest group influence does not seem to follow directly from group mobilization. Reported interest group influence on policy change was highest in the Kennedy administration and then declined in the 1970s, just as the advocacy explosion took off. Policy historians also find interest group influence where a few groups have large and consistent roles in policy making, rather than when lots of groups mobilize.

Relative interest group influence may also not follow from resource advantages. Monetary advantages on one side of a policy issue, the other key factor that scholars typically investigate as a determinant of interest group influence (see Baumgartner et al, 2009), was almost never mentioned by policy historians as an important determinant of interest group influence. PAC contributions also were rarely mentioned. These findings confirm those of a previous meta-analysis of case studies on interest group influence (Burstein and Linton, 2002). Advocacy groups were also seen as more influential than business interests, professional associations or unions, even though they are less numerous and have fewer resources. If these historical accounts are to be believed, it suggests that the mechanism for interest group influence is not likely to be resource exchanges.

These findings may help to explain the discrepancy between the common claims of interest group influence in case studies of policy making and the difficulty finding consistently influential tactics in the quantitative literature on influence. Scholars typically investigate influence by measuring the amount of interest group activity directed toward a specific tactic, such as PAC contributions or lobbying expenditures (see Baumgartner and Leech, 1998). If more groups and more resources do not lead to more influence, these measures should not be expected to be consistently associated with influence. Scholars often assume that all interest groups with the same resources and the same strategies should be equally likely to be influential. In other words, scholars investigate which groups succeed by comparing resources and strategies. If interest group influence typically results from general support offered by advocacy organizations with particular types of reputations, rather than resource advantages or the strategies that groups employ, these methods will not help us understand how some interest groups succeed where others fail.

To the extent that historical analysis of policy change offers a clear perspective on the mechanisms of interest group influence, it points toward the importance of a small number of central groups with reputations for constituency representation. This includes advocacy organizations representing important public groups, trade associations representing key industries and inter-governmental actors. This is consistent with evidence that interest groups seek to develop reputations for representing stakeholders (Heaney, 2004) and that the few interest groups that develop these reputations are repeatedly involved in policy making (Grossmann, 2012). The findings from the network analysis imply that these prominent interest groups are highly connected with one another but that most interest groups lie outside this subset of central actors.

Policy history offers a worthwhile and independent perspective from that usually found in studies of interest group influence, but that does not mean its findings are definitive. As a source of information on the policy process, several potential biases are likely to be found in policy history. First, like most observers of policy, historians may be less likely to notice policy making in administrative agencies and lower courts compared with laws passed by Congress, executive orders and Supreme Court decisions. Second, I have assumed some equality across policy changes of very different scope and importance by reporting frequencies from the population of all significant policy enactments. Footnote 16 There is an inherent difficulty in comparing across policy changes from different issue areas and historical periods. In addition, many policy actions of concern to some interest groups will fail to meet historians’ threshold for reporting on significant policy developments. The findings reported here apply only to significant domestic policy changes. Interest group influence on adjustments to particular provisions of policy may not make the cut, even though they would constitute a victory from the perspective of the relevant groups. For example, policy historians are unlikely to notice business influence on particularized tax breaks or university success in securing earmarks. Footnote 17

Another important difference between this analysis and previous interest group research is that I only analyze cases of successful policy enactments. Though some authors do present in-depth studies of attempted policy changes that failed, most do not. Even when discussing failure to change policy, most authors refer to a general attempt to solve a problem or advance a category of solutions, rather than pointing to a specific bill or regulation that was never enacted. When they do point to a specific proposal that failed, they choose the proposal that came the closest to enactment, making them less helpful comparison cases. The inherent limitation is that the analysis is based on only enacted policy changes. Close analysis of policy change over long periods should provide some expertise in identifying causal factors, but the lack of inclusion of null cases has particular implications for comparing these findings with traditional interest group research. An analysis of interest group influence on failures to enact policy, for example, would be likely to show more common influence from business interests. Yet failure to enact policy is the easier case to explain; the status quo bias is widespread in policy making, affecting interest groups and government actors (see Baumgartner et al, 2009). Nevertheless, the findings reported here only apply to reported interest group influence on successful policy enactments.

There are also some inherent limitations involved in aggregating the explanations of policy historians via the content analysis used here. I compile explanations across authors with varying breadth of focus and different standards for adjudicating influence. Some authors cite more explanatory factors and credit more actors than others. Although I have found few significant differences in the crediting of interest groups based on author discipline, issue focus or research methods, any differences may be amplified when I compile across authors and when more authors analyze some policy changes compared with others. Although I have found that these differences do not explain the results presented here, there remains unexplained variation in author judgments. Finally, the network analysis reported here relies on credit given to specific organizations for helping to bring about policy change. Not all ties in the networks convey political collaboration. The results are thus distinct from past research that analyzes networks of working relationships or coalitions.

Despite these limitations, policy history has several strengths that may help to correct for common problems in interest group research. First, it does not assume that the same set of tactics or the same level of resources deployed by different organizations will be likely to have the same effect. It points to the history of working relationships between policymakers and interest groups as well as to group reputations and ideas. Second, policy history regularly compares the policy influence of interest groups with that of various other actors throughout government. The lack of interest group influence may merely signal the greater importance of other factors, rather than the failure of interest groups. Third, policy history offers the perspective of reviewing policy development over an extended period to pick out the most significant events after policy decisions are taken. I am hopeful that these strengths will not only offset the limitations of policy history, but also ensure that this analysis provides a useful corrective to common approaches in interest group research.

Aggregating qualitative historical analyses of policy change offers a new picture of interest group influence in the policy making process. Research on federal domestic policy change, since 1945, indicates that interest group influence is common across venues, time periods and issue areas. Influence by advocacy groups through general support and lobbying is the most commonly cited factor. Nearly 300 specific interest groups have been credited with post-war policy changes, but most were infrequently involved. A few prominent groups, such as the AFL-CIO, the National Association of Manufacturers and the US Conference of Mayors, have been credited with many different policy enactments and play central roles in the influence network. According to historical accounts, interest group influence was common throughout most of the period, especially in the areas of civil rights & liberties, environmental policy, agriculture, and transportation.

These findings should encourage scholars to re-evaluate existing theories of interest group influence and the methods scholars use to judge them. Interest group influence may not follow directly from group or resource mobilization. Our measures of group activity may be unlikely to be associated with influence, even though a few groups regularly influence outcomes. General support for policy changes by interest groups recognized as stakeholders may be the most important route to influence. Scholars may not be able to analyze the most common type of influence without historical studies of how interest groups reach recognized positions in the policy process.

Interest groups likely play an important role in producing significant policy change. From the perspective of policy historians, interest group influence is quite common. Yet it may not be found in the places that interest group scholars usually look. Aggregation of explanations for policy change in historical narratives is one important method of assessing when, where, how and why interest group influence occurs. Given that it offers some different answers than traditional interest group scholarship, scholars need to assess whether the theories and methods of interest group research allow us to effectively assess the frequency or type of interest group influence.

The 14 issue areas cover the entire domestic policy spectrum, as defined by the categories used in the Policy Agendas Project. A complete breakdown of issues within each policy area is available at www.policyagendas.org/page/topic-codebook; accessed 24 March 2012.

Policy history is a nascent field of study that incorporates political science and history, but relies mostly on issue area specialists. Most of the authors see themselves as scholars of one issue area, such as environmental policy or education policy, rather than as historians or political scientists.

Because policy changes are often developmental, the major policy process frameworks recommend observing policy making for 10 years or longer (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, 1993; Kingdon, 2003). This enables considered retrospective judgments of influence.

The focus on significant policy enactments follows the emphasis of policy historians and scholarly convention (Mayhew, 2005). The findings do not extend to less significant policy change.

One notable exception is Michael Heaney's (2006) analysis of health policy coalitions.I found few significant differences in the extent or type of interest group influence based on the type of author or their discipline. University professors represent the vast majority of authors.

I compiled published accounts of federal policy change using bibliographic searches. I searched multiple book catalogs and article databases for every subtopic mentioned in the PAP description of each policy area. I then used bibliographies, literature reviews and suggestions from specialists. To locate the 268 sources used here, I reviewed more than 800 books and articles. Most of the original sources that I located did not identify the most important enactments or review the political process surrounding them. Instead, many focused on advocating policies or explaining the content of policy; these were eliminated. Sources that focused on a single enactment or covered fewer than 10 years of policy making were also excluded. Sources that analyzed the politics of the policy process from a single theoretical orientation without a broad narrative review of policy history were also eliminated. The population for the study is the sources that remained after these criteria were applied.

The agriculture category, Category 4 in the PAP, covers issues related to farm subsidies and the food supply. The civil rights & liberties policy area, Category 2 from the PAP, includes issues related to discrimination, voting rights, speech and privacy. The criminal justice area, Category 12, includes policies related to crime, drugs, weapons, courts and prisons. Education policy, Category 6, includes all levels and types of education. The energy issue area, Category 7, includes all types of energy production. The environment, Category 8, includes air and water pollution, waste management, and conservation. The finance & commerce area, Category 15, includes banking, business regulation and consumer protection. Health policy, Category 3, includes issues related to health insurance, the medical industry and health benefits. Housing & community development, Category 14, includes housing programs, the mortgage market and aid directed toward cities. Labor & immigration, Category 5, covers employment law and wages as well as immigrant and refugee issues. The macroeconomics area, Category 1, includes all types of tax changes and budget reforms. Science & technology, Category 17, includes policies related to space, media regulation, the computer industry and research. Social welfare, Category 13, includes anti-poverty programs, social services, and assistance to the elderly and the disabled. The transportation area, Category 10, includes policies related to highways, airports, railroads and boating.

US foreign policy decisionmaking may have unique determinants. It is assessed in a separate literature within international relations. The findings reported here do not extend to foreign policy.

The full list is available at www.matthewg.org/sources2012.docx; accessed 26 March 2012.Per cent agreement is the only acceptable inter-coder reliability measure for many different coders analyzing a single case.

Per cent agreement is the only inter-coder reliability measure appropriate for compilation of lists from an undefined universe where there is little similarity across cases.

I also adopt several conventions in the display of networks. Degree centrality, the number of links for each actor, determines the size of each node. I use spring embedding to determine the layout.

Many of these groups did not work alone, however; they were merely credited alongside legislators or administrators, rather than other groups.

State and local governments have to carry out the bulk of federal policy and, as a result, are often closely involved in policy making (Heclo, 1978).

Using a measure that differentiates among policy changes based on whether they constitute landmark policy changes, small incremental changes or enactments that fall somewhere in between, I have confirmed that the findings reported here generally hold across enactments of different sizes.

Although some readers may fear that policy historians would miss more significant cases of influence by businesses, unions and professional associations because of differences in the tactics of these groups, I did not find much evidence for this potential bias. Activities that were out of the public spotlight, such as direct lobbying, were referenced more often than constituent mobilization. Discussions of general support from interest groups also focused on internal negotiations more often than public endorsements and media coverage. Despite this focus, policy historians were simply more likely to credit advocacy organizations than other groups. Moreover, they tended to credit broad peak associations with reputations as major representative stakeholders, such as the Chamber of Commerce, the AFL-CIO and the National Association for Manufacturers, even when they did credit business interests or unions. Policy historians may still be collectively incorrect to focus on large groups with established reputations, but they did not do so because they focused on public advocacy at the expense of lobbying outside the spotlight.